In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

I’ve always found that one way to feel better about your life is to read a story about someone with even worse problems than you, and seeing how they overcome those difficulties. Time travel stories are a good way to create problems for fictional protagonists. The author drops a character into a strange new environment—something challenging, like the waning days of the Roman Empire, for example. They will be equipped only with their experience in the modern world, and perhaps some knowledge of history or technology. And then you see what happens… Will they be able to survive and change history, or will inexorable sociological forces overwhelm their efforts? And when that character springs from the fertile imagination of L. Sprague De Camp, one of the premiere authors of the genre, you can be sure of one thing—the tale will be full of excitement, and a lot of fun, to boot.

The first science fiction convention I ever attended was ConStellation, the 41st World Science Fiction Convention, held in Baltimore in 1983. A Worldcon is certainly an exciting way to enter the world of fandom. My father and brother took me on a quick tour of the huckster room, then whisked me off to a small group meeting with one of my dad’s favorite authors, L. Sprague De Camp. I found this exciting, as I had read a few of De Camp’s works, and knew him as the man who rescued Robert E. Howard’s Conan from obscurity. The event was held in his room, a crowded venue, and his wife Catherine was uncomfortable being a hostess without any resources to entertain the visitors. The author himself lived up to every preconceived notion I had about writers. He was tall and patrician, dashing even, with black hair flecked with gray and a neatly trimmed goatee. I can’t remember his attire, but he wore it nattily. I seem to remember a pipe, but that might just be a memory from book dust jacket photos. He was witty, erudite, and told some fascinating stories. He had the group in the palm of his hands, and before we knew it, our hour was done. When you start your fan experiences with a Worldcon, it is hard to go anywhere but downhill, and when the first author you meet up close and personal is L. Sprague De Camp, the same rule applies. Before or since, it has been a rare treat when I have met anyone even half as impressive as De Camp.

About the Author

L. Sprague De Camp (1907-2000) was a widely respected American author of science fiction, fantasy, historical fiction, and non-fiction. His higher education was in aeronautical engineering, but he was widely versed in many fields—a modern-day Renaissance man.

De Camp’s first published story appeared in Astounding Science Fiction in 1937, but John Campbell’s companion fantasy magazine, Unknown (started in 1939) gave De Camp a venue that better suited his imagination. He was a frequent contributor to both Astounding and Unknown, becoming one of the stable of authors editor John Campbell favored during the period that many call the “Golden Age of Science Fiction.” His work was known for intellectual rigor, for well-staged action scenes, and especially for its wit and humor.

In 1939 De Camp married Catherine Crook. They remained together until her death just a few months before his. She was a writer herself; they sometimes collaborated. He was commissioned in the Navy Reserve during World War II, worked alongside Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov on special projects at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and attained the rank of Lieutenant Commander.

In later years, De Camp turned more to fantasy than science fiction. One of his greatest accomplishments, writing with Fletcher Pratt, was the humorous fantasy series featuring the character Harold Shea, the first book of which, The Incomplete Enchanter, came out in 1941. When the publication of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings created a new market for heroic fantasy, De Camp helped resurrect Robert E. Howard’s pulp magazine tales of the warrior Conan, editing Howard’s work, finishing tales from Howard’s fragments and notes, and writing new tales himself. Conan became wildly popular, with many new books being added to the series, and movie adaptations based on the character. Some have criticized De Camp’s rewrites as meddling, but without his efforts, the character may have never re-emerged from obscurity (and for purists, Howard’s work in its original form is now widely available).

De Camp was prolific and wrote over a hundred books. Over forty of these works were novels, with the others being non-fiction on a variety of subjects. He wrote many books on science, history, and engineering topics, my favorite being The Ancient Engineers, which should be given to anyone who thinks ancient aliens were behind many of mankind’s historical accomplishments. He also wrote well-received biographies of Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft. His own autobiography, Time & Chance: An Autobiography, won De Camp’s only Hugo Award in 1996.

De Camp was voted by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America to receive the Grand Master Award, and was also recognized by fans with a World Fantasy Convention Award. He is buried in Arlington Cemetery with his wife Catherine.

Adventures Through Time

Time travel is a perennially popular theme in science fiction. There are journeys back in time, journeys forward in time, journeys sideways in time, and a whole plethora of tales that center on the various paradoxes that time travel could create. Readers have an endless fascination with exploring the impact a time traveler might have on history, or just the impact that living in the past could have on the travelers themselves. Moving forward in time gives us glimpses of what might happen, and these tales often contain a cautionary element. Moving sideways in time gives us the chance to look at alternate worlds, where history led to a world different from our own. The online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has an excellent article on the theme of time travel, which you can find here.

Buy the Book

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

In this column, I have reviewed a number of other time travel adventures. Sideways in time adventures (a favorite of mine) have included Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen by H. Beam Piper, A Greater Infinity by Michael McCollum, and The Probability Broach by L. Neil Smith. I looked back in time with S.M. Stirling’s Island in the Sea of Time. And I looked at time travel attempting to head off disaster with Armageddon Blues by Daniel Keys Moran. There have been several other time travel tales that have come up in anthologies, but being a linear thinker, I tend not to care for fiction that focuses at the mechanics of time travel, or the paradoxes it creates.

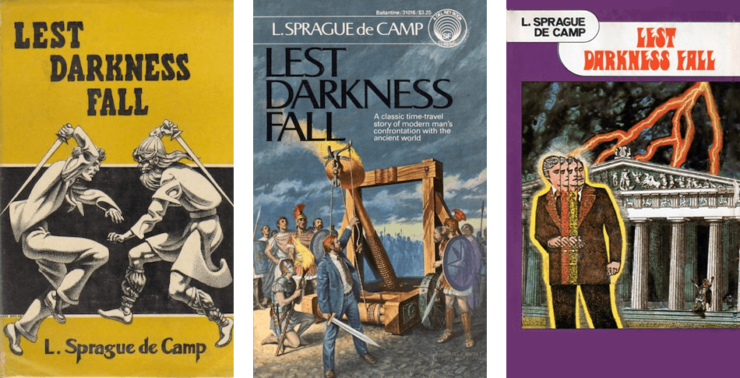

Lest Darkness Falls is one of the earliest, best, and most influential time travel tales in classic SF, and centers on one person trying to change history. A shorter version of Lest Darkness Fall appeared in Unknown during its first year of publication, followed by a hardback edition in 1941, and the book has been in print pretty much ever since. Lest Darkness Falls shows how modern persons can apply their knowledge to the past in a way that has a huge impact on history. But not all De Camp’s time travel stories were so optimistic. His later story “Aristotle and the Gun,” for example, which appeared in Astounding in 1958, portrays a time traveler with great ambitions for changing the current world, but whose actions, and the disastrous response of the world of the past, do not result in anything approaching the consequences he’d initially planned.

Lest Darkness Fall

We are introduced to Martin Padway, a mild-mannered archaeologist who is being driven through modern Rome by an Italian colleague with an interesting theory: that various missing persons have slipped back in time, but we don’t see the world change because their presence creates a branch in history. De Camp’s witty touch is present right from the start as he describes the hair-raising behavior of the Italian drivers the pair encounter. How the time travel actually happens is not explained, but during a lightning storm, Martin suddenly finds himself in the past. He is in a Rome with no cars and no electricity, and from the language, attire, and other clues, realizes he is in the latter days of the Roman Empire. It is clear that De Camp has done his homework, and he brings the world of Sixth Century Italy vividly to life. The language spoken here is partway between classic Latin and modern Italian, and Padway is soon able to communicate in a rough manner. He goes to a money changer, finds a place to stay, and acquires clothes that make him a bit less obtrusive. Martin then goes to a banker with an interesting proposition: If the banker will give him a loan, he will teach his staff Arabic numerals and algebra. This is different from many other tales in this sub-genre, in which engineering, technological, or military knowledge is used by the time traveler. But those wouldn’t fit the bookish nature of Padway’s character as well as skills like double-entry bookkeeping.

Padway finds that he has arrived after the invasion of Rome by the Ostrogoths, who left Roman society largely intact. But he knows that the Eastern or Byzantine Empire will soon be invading, with their forces led by the famously competent General Belisarius, and the subsequent wars will be devastating. Padway is not an especially altruistic character, but in order to save himself, he must do what he can to stave off this catastrophe.

He builds a printing press, and in addition to printing books, he decides to start a newspaper, which gives him immediate political influence. And he convinces some rich and powerful people to invest in a telegraph system that will link the country with information. He assembles telescopes, needed to minimize the number of towers for his new telegraph, and then uses that new invention to gain favor from the Ostrogoth king.

I could go on at length about the many fascinating characters, scenes, and situations that populate this book, as these portrayals all speak to De Camp’s considerable strengths as an author. But that would rob new readers of the fun of encountering them when reading the book. I should note that like many other science fiction books written in the mid-20th century, there are few female characters. There is a maid that Martin abandons after a one-night stand because her hygiene offends him. And later in the narrative, he falls for an Ostrogoth princess, and actually starts talking marriage until he realizes she is a pre-Machiavelli Machiavellian, full of murderous plots to amass power. He adroitly puts her in contact with a handsome prince, and then gracefully admits defeat when she falls in love with this new suitor.

When war comes, Martin finds himself drawn into statecraft and military leadership at the highest levels. He has some knowledge of history, of course, which some see as a magical precognitive power, but as his presence affects and changes history, his predictive powers begin to wane. And while his efforts to make gunpowder fail, he does have some knowledge of tactics that can be used to defend Rome from the catastrophe that threatens…

Final Thoughts

I have been more cursory than usual in recapping the action because I strongly urge everyone who has not discovered this book to go out, find a copy, and read it. It is even better than I remembered, has stood up remarkably well over time, and is a fun adventure from beginning to end. De Camp is one of the greatest authors in the science fiction and fantasy pantheon, and this book is among his finest.

It is fascinating to read how Martin Padway, an ordinary man, rises to the occasion and heads off disaster on a massive scale. It reminds us all that ordinary people, if they have courage and perseverance, can have a positive impact on history—an important lesson for the times in which we live.

And now I turn the floor over to you: Have you read Lest Darkness Fall, or other works by L. Sprague De Camp? If so, what did you think?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

I have read all his Conan books; I devoured the Harold Shea books; and Land of Unreason was great fun. I now must find and read Lest Darkness Fall.

“various missing persons have slipped back in time, but we don’t see the world change because their presence creates a branch in history.”

A remarkably modern take on time travel theory.

I’d say that the breadth of knowledge that Padway uses to bring about his various changes is a bit too broad, but I suspect that every last one of them is something de Camp knew and would have been in a position to try were he in Padway’s place.

In a way, it’s too bad that de Camp has become so closely connected with the Conan revival. A lot of his other work has fallen by the wayside in the last couple of decades, and that’s a shame. My particular favorites are the five historical novels he wrote in the late 50s. An Elephant for Aristotle and The Dragon of the Ishtar Gate in particular are very good.

I remember reading this book, quite a few years ago. A minor spoiler: one of the inventions he produced was soap ;)

Love this book, and I think I’ve owned all those editions. Am I the only one who decided to learn things, so I would be prepared when I went back in time?

My favorite bits- Martin’s answers to questions about religion, and how he knows the latest gossip, which to hm is history.

@5 I remember looking up the formula for gunpowder after reading H. Beam Piper’s Gunpowder God in Analog when I was a kid. Just in case… :-)

The other great story that should be mentioned is The Man Who Came Early, by Poul Anderson, which is the response to this and many other white saviour style time travel books. In it the engineer hero steadily and repeatedly offends his hosts and digs himself deeper and deeper into a hole by misapplying his future knowledge to a setting incapable of using it.

Pam@5: Am I the only one who decided to learn things, so I would be prepared when I went back in time?

Most assuredly not!

@6,

Gunpowder’s recipe is pretty easy, but getting it right is a bit more difficult. I’ve also taken organic chemistry, which means that, hypothetically, I can make all sorts of dangerous stuff. I also didn’t take the lab, so I’m more likely to either fail miserably or spectacularly.

I enjoyed “Lest Darkness Fall” and I have found pretty much anything by De Camp is worth reading. Among my personal favorites are his historical novels (titles include “An Elephant for Aristotle”, “The Arrows of Hercules”. “The Bronze God of Rhodes” and “The Dragon of the Ishtar Gate”). “The Dragon of the Ishtar Gate” is particularly enjoyable since it could easily have been written as an epic fantasy. The Conanesque hero is saved at the last minute from a horrible death so he can be sent off on a near impossible quest at the command of the King. The King is seeking an immortality potion and his pet wizard has promised him one…if he can get the ingredients. At the top of the list is “the blood of a dragon”. So our hero is dispatched to the sources of the Nile where such dragons are rumored to live. And he must capture it and bring it back alive (that dragon’s blood must be fresh, you know). What they don’t tell him is that there is another key ingredient on the wizard’s list: “the heart of a hero.” So the hero and his wily lieutenant (a Greek who is a master of what, by Persian standards, are the arcane arts of literacy, logic and an understanding of compound interest) fare forth. The King in question is the historical Xerxes, ruler of the Persian Empire. And don’t miss De Camp’s end note where he points out the compelling archeological evidence that someone at that period did actually make such a remarkable journey (from Persepolis to central Africa and back again).

To Mayhem @7 above: “The Man Who Came Early” is a powerful story. The key line in it is when the hero, having realized that there is no way he can make his “Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” visions a reality in 10th Century Iceland, says in despair “You haven’t got the tools to make the tools to make the tools!”

I remember L. Sprague de Camp fondly, if not one as of The Great Ones. I never got around to Harold Shea stories; probably my window of opportunity to enjoy them has long since closed. I don’t I ever finished Lest Darkness Falls. But I did like the Novarian series as a teenager, although recall finding Jorian’s clever folktales about the kings of Kortoli more entertaining than the story itself. I’ve never revisted these books, and suspect they’d date about as well as, say, Xanth.

I get the impression that Robert E. Howard purists see de Camp as a villain for the bastardized and pastiched Conan that he was responsible for, and also for his biography of Howard. My heart agrees with them, but my head says that few, if any, of them would ever have become Howard purists without him. A bit of gratitude seems appropriate, even if (like me) you only prefer the originals.

If there’s one book by de Camp I still wish to read it’s non-fiction: The Ancient Engineers. Fascinating subject, and de Camps’s treatment appears to be regarded as a classic. (Interesting side note: The Ancient Engineers is also alleged to be the one book mentioned by name in “Industrial Society and Its Future,” better known as “The Unabomber Manifesto,” by Ted Kaczynski.)

I just also remembered de Camp’s short story “A Gun For Dinosaur,” about time traveling big game hunters. Looking back, I think that, loosely adapted like Westworld or The Man In the High Castle, it would make a great premise for a TV series. (That is, if the coronavirus hasn’t killed big budget live action television.)

Speaking of soap I seem to recall soap and a recipe is found in Homer? The Enchanter books are likely to be less popular as the sources/references are themselves less popular.

It’s kind of amusing that the first thing that from-1930s Padway makes in the 6th century is … a still. I suspect de Camp was thinking about his own college days during Prohibition.

As for Padway’s relationships with women – damn, he is such a nerd. None of them work.

This one is a perennial favorite of mine, and I was happy to read a couple of new books last year that reminded me of it in different ways: K. J. Parker’s Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City and Scott Warren’s The Dragon’s Banker. Both feature somewhat Padway-esque protagonists who have to try to stay above water with one clever scheme after another. The setting of Parker’s novel also has a very Late Roman/Byzantine flavor to it, for good measure.

@12

It’s never too late to enjoy Harold Shea. I probably approach it differently now than when i was in college but you should give it a try.

Like you, my introduction to fandom was with Sprague & Catherine. The first con I went to was Balticon in 1984, held at the Hunt Valley Inn in Cockeysville. After I got there and looked around, I looked thru the Pocket Program and saw a listing for a Panel entitled “An Hour with L. Sprague DeCamp & Catherine Crook DeCamp”. It was an hour long program item in a medium sized program room. Sprague & Catherine sat at the head table and the room was about half full (many people were waiting in line for the Masquerade). Sprague was nattly dressed and courtly and full of fun stories and Catherine was relaxed and also funny. And for a hour they took questions and went over old times, telling stories about their books and stories and about their friends (Like Issac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Frederik Pohl and Ron Hubbard. All in all, great fun.

@@@@@ 17 Dr. Thanatos, maybe some day, but there’s so much to read in a lifetime.

I’ve got all the historicals, Lest Darkness Fall, the Harold Shea and various others mentioned upthread. Phoenix Picks/ARC Manor have published the historicals and Lest Darkness Fall as ebooks, so they should be relatively easy to find. I still find these easy to read albeit a bit dated in style (and lack of female representation). I’ve got some of his non-fiction as well which is pretty good – especially Places of Mystery (how to debunk the New-Agers).

However, I think the Harold Shea would be rather dated now – I recall some rather stereotyped characters, and I haven’t read the Novarian series in many years.

Talking about Fletcher Pratt, his non-fiction is good too – Secret and Urgent, about cryptography. Obviously it pre-dates computerised cryptography, but it’s a pretty good introduction to historic methods.

One of my favorite books in my boyhood was a Civil War book by Fletcher Pratt. Imagine my surprise when I discovered he wrote SF as well.

Yesterday I found a few boxes of books forgotten in a corner of the basement, including enough good ones to keep this column busy for a couple years. And one was the Harold Shea adventures, a happy coincidence!

Two novels that use historical subjects that also changed my views of the past are Lest Darkness Fall (which revised my perspective on Justinian’s reconquest for the worse) and The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara (which revised not only my perspective but seems to be a ‘Jonbar point’ if you will in American Civil War studies regarding the roles of Gens. Lee and Longstreet). The Dragon of the Ishtar Gate looks like a book to add to my TBR pile(s).

The Dragon of the Ishtar Gate owed something of a debt to Willy Ley’s Exotic Zoology, as I recall, although it’s been a while since I read it. Ley draws parallels between the Babylonian sirrush and the contemporary (but probably imaginary) mkole-mbembe of the Congo Basin.

There was a bit in the Ley book about a Central African pygmy having reached the court of one of the Pharaohs, as well. At least, he looked like a CA pygmy – the Pharaoh commissioned a statue of him, which survives, as does some text describing him. But it’s possible that he was a member of a group that lived closer to the sources of the Nile, that we now have no trace of. In either case, his presence demonstrates that some cultures of the Ancient World did have at least a bit of knowledge of far-off places, as does the king’s dragon issue.

I’d expect the much later shared universe Harold Shea to be mixed as is the nature of a shared universe. Particularly in the early first collaboration the universe of the Faerie Queen from Spenser with an S to drag in another literary reference has a number of women with lots of agency – as only to be expected from a source Raleigh subsidized in praise of Elizabeth I.

Eventually 40 years later much of the shared universe reworked plot is rescuing damsels in distress but given that reworking once very popular source material is the whole idea I’d be reluctant to complain that Orlando Furioso or Arthur of Round Table Fame or Yngvi the louse appear in other works by other authors at other times. As with say Silverlock I’d argue that a certain lack of originality in many characters is more a strength than a weakness.

And I stand by my earlier remark above that failure to know the source is more likely to detract than ignorance and coming on the characters fresh is to increase the reader’s joy.

As I recall, it has an odd omission that played in Harry Harrison’s A Rebel in Time. Antagonist Wesley McCulloch uses the Pratt text as his guidebook to the Civil War period. As it happen, there’s a famous incident not mentioned in the text, which why McCulloch has no idea he should avoid Harper’s Ferry on October 16, 1859. There are consequences…

One thing that got me on my most recent reread of Lest Darkness Fall was that as the stakes grew bigger, the book became less character-centric and more plot-centric. Instead of learning what Padway did and why, we just get what he did.

I realize that in his era, you couldn’t have 500-page doorstoppers, but it reduced my enjoyment of the book.

IIRC that someone (David Drake?) did a semi-sequel – Lest Darkness Fall and Related Stories.

@26: Drake is one of 3 authors who wrote semi-sequels collected in the book you mention. The others are Fred Pohl and SM Stirling. I don’t remember much about them or who wrote what, other than one where Padway is taken to the future to see what he achieved. Mostly, they felt like padding to bring a short novel up to a length people would be willing to shell out money for.

@27, DemetriosX:

Drake is one of 3 authors who wrote semi-sequels collected in the book you mention. The others are Fred Pohl and SM Stirling. I don’t remember much about them or who wrote what, other than one where Padway is taken to the future to see what he achieved.

You’re probably thinking of S.M. Stirling’s The Apotheosis of. Martin Padway.

http://indbooks.in/mirror1/?p=378713